In my last post, I examined Michael Walzer’s treatment of the Problem of Dirty Hands with regards to how it works for soldiers. In this post I want to examine some points in Suzanne Dovi’s criticism of Walzer’s treatment.

One of Dovi’s criticisms of Walzer is that, as she says it, Walzer owes “an unacknowledged debt to to political actors who are unwilling to violate their moral principles.” (p. 129) I will sidestep (at least for now) questions of whether she is actually arguing with Walzer at all, or how her definition of political actor differs from his, or any of the great points that came up in discussion.

Even before I made it to Part III, where Dovi talks specifically about Pacifism and Just War theory, as I read her making her case for how absolutists help keep up the moral health of the state, I was already thinking of Jeanette Rankin.

Jeanette Rankin was a Republican Representative from Montana. She was also the first woman elected to Congress, and an outspoken pacifist. Among her thoughts on the subject of war: ““You can no more win a war than you can win an earthquake.”

Rankin only served two terms. First elected in 1916, she arrived in Washington amidst calls for U.S. entry into the [First] World War. On 6 April 1917, when the House of Representatives voted on a resolution declaring war on Germany, Rankin voted ‘no,’ one of only fifty Representatives to do so. She decided to run for the Senate in 1918 (having been placed into a heavily Democratic Congressional district by redistricting,) and was defeated, but she was re-elected to the House in 1940. That’s right–once again, Jeanette Rankin arrived just in time for a march to war.

Zanesville (OH) Signal Evening Edition, 8 December 1941 Note highlighting of Rankin as a woman, even though nine other women (one Senator and eight Representatives voted for the resolution.

On 7 Dec 1941, the Japanese Combined fleet attacked Pearl Harbor in the Territory of Hawaii. The next day, President Franklin Roosevelt asked Congress for a Declaration of War against Japan. Of the 470 Senators and Representatives, only Rankin voted against the declaration. Beyond her pacifist track record, she said, “As a woman I can’t go to war, and I refuse to send anyone else.”

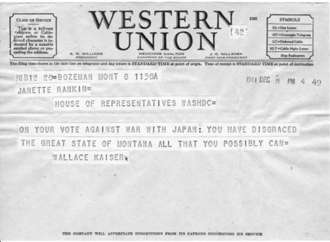

This stance was obviously not a popular

one: Less than a day after 2,400 Americans were killed and 1,100 wounded in the surprise attack, and with Japanese forces attacking U.S. forces in the Philippines, even the famously isolationist members of Congress were clamoring for war. After the vote, an angry mob chased Rankin through the Capitol. People called her names like “Japanette Rankin,” and she received angry telegrams and letters. She didn’t run for re-election in 1942. But even in later life, she never regretted the stance.

So what do we make of this? Certainly, Rankin was a absolutist on the question of war. She took a stand, and by so doing certainly added a dimension to the public discourse that wouldn’t have been there otherwise. I’ve heard people try to make the argument that she may have wanted to ensure that the United States didn’t go to war with a unanimous vote. An interesting notion, certainly, but I’ve never seen anything from her hand or mouth to validate it. Clearly, an attack against on a Territory of the United States was the clearest casus belli possible–no stance other than her absolutism would ever suggest ignoring an act like this. Just as clearly, there was no danger that her “no” vote would affect the outcome. In this case, Rankin got to vote her conscience with no danger other than the scorn of the public.

I don’t mean to sound too critical of Rankin. I admire her desire to stick by her principle, even though particularly in the case of the 1941 vote, her principles may have run up against her responsibilities. It’s also very true that Rankin’s votes give us a reference point to discuss the votes for war, and thereby widen our discussion (although in this case, it didn’t do so in the moment.) But consider for a moment: does it really require an absolutist to do that?

Admittedly, I don’t think Dovi is actually saying it is necessary to be an absolutist to do so, but she does state that they are useful for expanding the range of options.

In the movie Thirteen Days, a scene plays out where the members of the Executive

Committee are briefing President Kennedy on the results of their deliberations on responding to the Soviet missiles in Cuba (about 37:30). The majority opinion is for a naval blockade (or quarrantine) of Cuba, and the minority are counseling air strikes; both options have a high probability of war. Then the following exchange takes place:

President Kennedy: [summarizing their options] So quarantine, or air strike?

[Ambassador to the United Nations] Adlai Stevenson: [clears throat] There, uh, there is a third option. With either course we undertake the risk of nuclear war, so it seems to me that maybe one of us in this room should be a coward… so, I guess I’ll be. A third course is to strike a deal: We trade Guantanamo and our missiles in Turkey; get them to pull their missiles out. We employ a back channel; we attribute the idea to [U.N. Secretary-General] U Thant. U Thant then raises it at the UN.

President Kennedy: I don’t think that’s possible, Adlai.

Following the meeting, the President’s brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, complains that Stevenson is advocating for appeasement and that he isn’t up to the challenge of the crisis. While the film takes some artistic liberties, in real life those criticisms of Stevenson were voiced in the media as early as December of that year.

Funny thing is, war was avoided by just the kind of compromise Stevenson suggested.

No one would ever call Adlai Stevenson an absolutist. An adept politician, the New York Times noted on his death that “he was a realist at dealing with essential political compromise. But when moved deeply by principle he risked political sabotage and personal obloquy for his convictions.” If he could bridge that divide, why can’t more politicians do it?

Thank you for your thought provoking and well researched post! I, too, believe that Dovi was not necessarily indicating that an absolutist is required in every political instance, but that certain flexibility toward a compromise of some sort is necessary if we are to meet certain challenges. I also appreciate how you point out that while Rankin took her lumps for several of her congressional voting choices, she refused to abandon her principles even years later.

I, like Adlai Stevenson, am from Illinois. While growing up, I notice he is seen as a hero for a variety of his political choices. You are correct when you note that while “no one would ever call [him] an absolutist,” he too made several unpopular calls, such as the one you note above. However, he was considered a model for what is determined to be an “adept” and capable politician.

As you point out, what I find so disturbing in today’s political arena is the lack of compromise and consideration. Today, our current Congress has little regard for the various views offered by others, which reflects poorly on the constituencies, they represent and which ultimately, do not serve any of us well. Consistently, prominent media outlets have conducted survey after survey indicating that for the past 10 years, we have had a “do nothing Congress” which should be voted out. While we the voters always want to remove them from their respective offices, we don’t because as someone else said in our class “I wouldn’t want to be in their shoes for anything in the world.”

Beyond their common vitriolic behavior, I guess we could ask ourselves comprehensively, if we had the chance, would we walk in their shoes? What could we, if elected, do differently to end the stalemates and constant vitriol? Is it possible to end the constant bickering and party battles in an effort to end the divide you point out?

Thanks for the comment! Yes, the Congress we have today is a far cry from the Adlai Stevensons of the world. The sad part of it is that, more often than not, when someone mentions the need for compromise, it’s always the other side that should compromise. That’s not just the politicians, but increasingly, the pundits and even the voters seem to say that. When a politician makes any kind of compromise, how often do they get “primaried out” by someone promising that they won’t compromise? It appears that as a society, we’re embracing the idea that compromise is a bad thing, and that doesn’t bode well for the question you ask about ending the bickering.

Interestingly, to return to Dovi for moment, one of the ways she says absolutists are helpful is in making moderate compromise positions more acceptable. That breaks down, however, when the absolutists start running everyone else off the field. That in turn gives us another question to answer…is her observation a good one theoretically, and only foiled by an unhealthy attitude in our society, or is her observation unrealistic and “Pollyannaish?”

Good Evening! I appreciate the well put together post! I haven’t seen Thirteen Days in a very long time, and suddenly I’m getting the itch to watch it. I think you are correct in your belief that it does not require an absolutist to propose such a radical idea as Stevenson did – It is not so much the person or the belief system, but the idea and the position that matters. But in today’s political spectrum where most politicians (I should say political actors) are terrified of compromising with those that might be seen as the “enemy,” having absolutists certainly simplifies the equation. Having anyone that is willing to speak outside of the two political parties is a rarity now, whether they are what we would call an “absolutist” or not. – but it does as Dovi says and increases the range of discussion.

Thanks for the comment. You’re definitely right that the idea being considered is definitely the important thing to consider. If we have to make a decision and have two or three positions to consider, we should consider them on their merits, not on how strongly people believe them. I agree its hard to find people that advocate intermediate positions anymore. In fact, I think when Dovi says that absolutists increase the range of discussion she does so from an expectation that most political actors are willing to compromise. So the situation we’re talking about kind of turns that on its head.